Mount Fuji behind Cherry Trees and Flowers, Katshushika Hokusai

Mount Fuji behind Cherry Trees and Flowers, Katshushika Hokusai

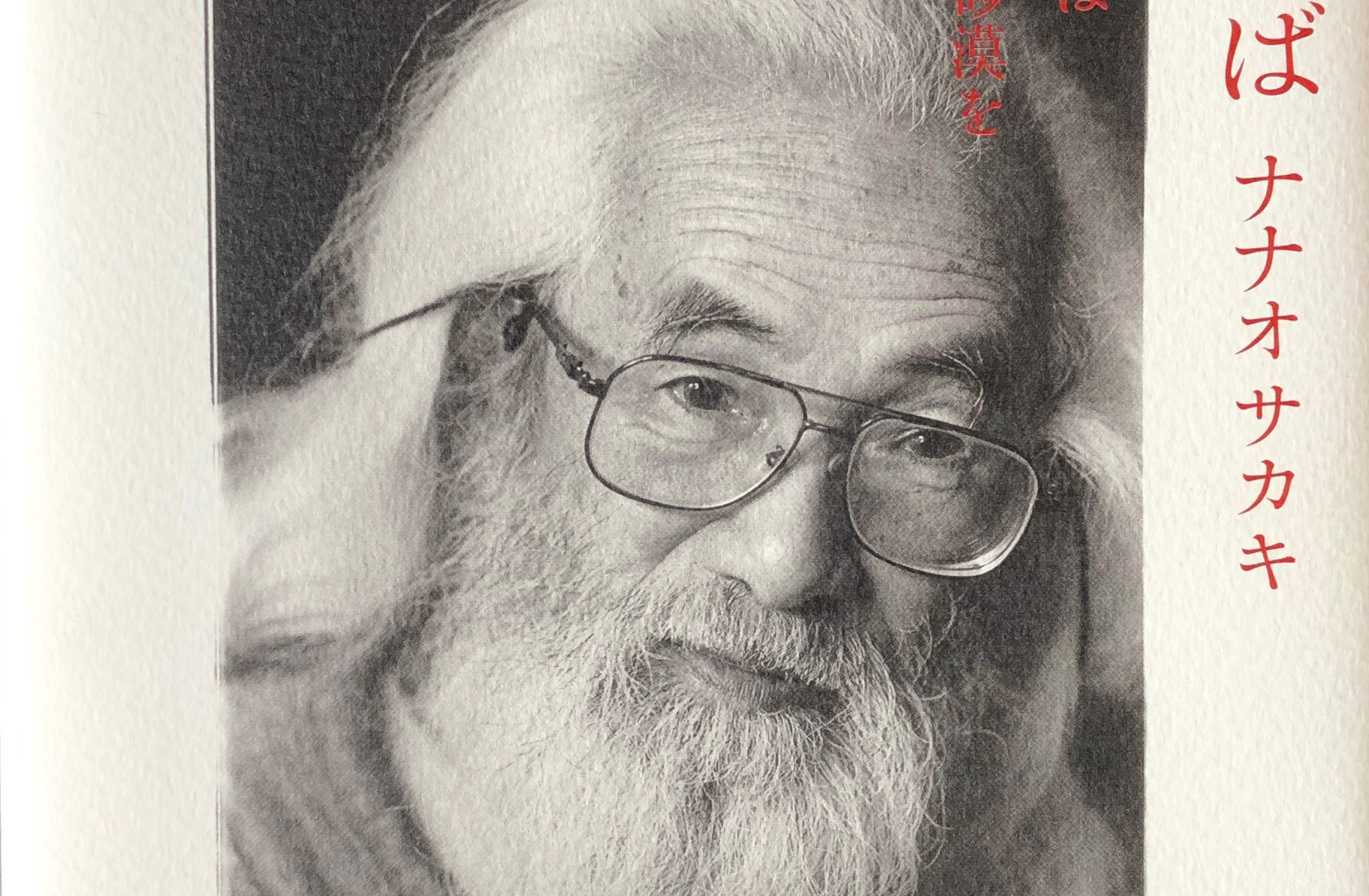

Who was Nanao Sakaki? More than a decade after his death, that question is not easy to answer – mostly because he was a little bit of everything, all the while refusing to be anything. A Zen master, a wandering philosopher, a Beat poet, a counter-cultural leader, an unrelenting environmentalist and a passionate traveler – these are just some of the designations that have been given him throughout his long life. Born in 1923 into a rigid, militaristic Japan, he joined the army at an early age, which was a common course for the young men at the time. During the Second World War he worked as a radar technician stationed on the island of Kyushu, where he would spend his days cooped up in a concrete bunker, staring at radar screens. All the while, his urge to be outdoors and roam wide open spaces, as well as the first tenets of his anti-establishment sentiment, were brewing inside him.

After the war, Nanao Sakaki went to Tokio and found a job in the publishing industry. However, after a year he decided that it was not the kind of life he wanted for himself. He quit his job and started living on the street as a homeless person. That is when his obsession with walking started. He spent his days walking all around Tokio, which back then was already one of the largest cities in the world. Then he started going out of town and walking to the nearby towns and cities, and then farther and farther. He traveled extensively all over Japan, often on foot, until he found a small island of Suwanosejima, where he decided to start a farming commune based on the idea of rural life far from the materialistic world that he left behind. He and his small counter-cultural commune, known in the West as the Tribe, came to prominence when the government decided to build the airport on their island; they protested, wrote poems about the environmental destruction of Japan, held rallies and even went to San Francisco to find international support for their activism, mostly thanks to Gary Snider, American poet fascinated with Japanese culture, who introduced Nanao to Allen Ginsberg and other poets from the American Beat circle.

The concept of a wandering, vagrant sage has a long tradition in the Far East.

They invited Nanao Sakaki to visit America, where he spent around ten years in total, mostly in California and New Mexico. In this period, Nanao did exactly what he used to do in Japan before that: he lived freely, homeless and jobless, relying on the hospitality of his friends, writing poetry – and walking. He is reported to have walked from California to New York and back, and even all the way up to Alaska, but as he was mostly on his own and did not like to discuss how he spent his time, these accounts are impossible to verify. It is safe to assume that he walked a lot, spending days, months and years on the road. He often stayed at Zen Center in San Francisco, where he was known for never having any money, private property or a place of his own; however, as he just read books, discussed philosophy and wrote poetry, never doing any community work or even washing the dishes, after a while he would overstay his welcome and move to another hippie commune, which were numerous in California at that time.

Nanao Sakaki on the cover of one of his books.

Nanao Sakaki on the cover of one of his books.

The concept of a wandering, vagrant sage has a long tradition in the Far East. The sage is a poet, a monk, a teacher or a philosopher – and most often all of that at once. He renounces the rigid societal rules and the materialistic world, and roams the world in pursuit of knowledge, at the same time learning new things and sharing his wisdom with those he meets on the road. Probably the most famous from the line of wandering poets-philosophers in Japan was Matsuo Basho, who lived in the 17th century. In fact, many similarities can be found between Nagao Sakaki and Matsuo Basho: their renunciation of the society, their fascination with the natural world, and their love of walking.

Matsuo Basho by Katshushika Hokusai, 18th century.

Matsuo Basho by Katshushika Hokusai, 18th century.

Nanao Sakaki’s walking was a part of his Zen worldview, which advocated personal freedom, environmental activism, and spending time outdoor. In one interview, recounted in the book “Nanao or Never”, Sakaki tried to explain the kind of Zen he followed: “Most Zen is uninteresting to me …It’s too linked to the samurai tradition – to militarism. This is where Alan Watts and I disagreed: he didn’t fully understand how the samurai class with whom he associated Zen were in fact deeply Confucian: they were concerned with power. The Zen I’m interested in is China’s Tang dynasty variant with teachers like Lin Chi. This was non-intellectual. It came from farmers - so simple. Someone became enlightened, others talked to him, learned and were told, Now you go there and teach; you go here, etc. When Japan tried to study this kind of zen, it was hopeless. The emperor sent scholars, but with their high-flown language and ideas, they couldn’t understand what it was about.”

To stay young,

To save the world,

Break the mirror.

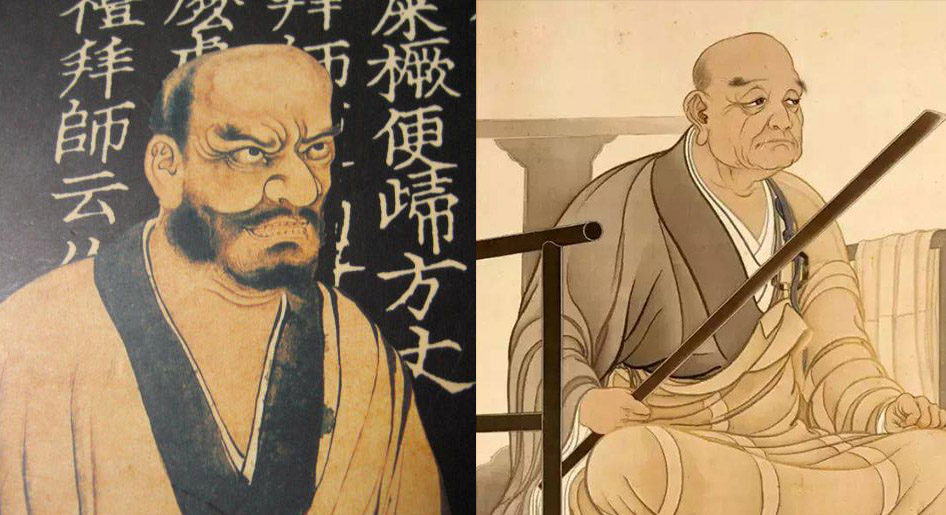

Lin Chi is the Japanese name of Linji Yixuan, a Chinese sage who lived in the 9th century. He was known as the founder of the Linji school of Buddhism. Remembered as a rebel Zen-master who preaches the wordless truth, Lin Chi was focused on trying to explain his teachings without getting mired into words, which he considered useless and misleading, as the true essence of the world lies beyond concepts and ideas. To that end, he taught relying on non-conceptual forms of expression, allegedly shouting and even hitting his students to help them reach enlightenment. The Linji school eventually spread to Japan where it gave rise to the Rinzai school, one of the three main denominations of Zen in Japanese Buddhism.

Two very different representations of Linji Yixuan (Lin Chi), the Chinese Zen master renowned for using his stick as a didactic tool.

The recurring themes in Nanao Sakaki’s poetry are related to the natural world: forests, rivers, deserts, jungles, oceans, mountains, and mankind’s relationship with that world. He lamented the destruction of Japan’s nature, the deforestation and cementing of the riverbanks and sea shores, the engineering and building mania that caused a rift between man and nature.

After returning to Japan, Nanao Sakaki settled down in the mountains, where he spent the rest of his life walking in nature and writing poetry; he lived to be 81. Several of his poetry collections have been translated into English, thanks to his friends in the American Beat circle.

*

If you have time to chat,

Read books.

If you have time to read books,

Walk into mountain, desert and ocean.

If you have time to walk,

Sing a song and dance.

If you have time to dance,

Sit quietly,

You lucky, happy idiot.

*

Soil for the legs

Axe for the hands

Flower for the eyes

Bird for the ears

Mushroom for the nose

Smile for the mouth

Song for the lungs

Sweat for the skin

Wind for the mind.

*

In the morning

After taking cold shower

- what a mistake -

I look at the mirror.

There, a funny guy,

Grey hair, white beard, wrinkled skin,

- what a pity -

Poor, dirty, old man,

He is not me, absolutely not.

Land and life

Fishing in the ocean

Sleeping in the desert with stars

Building a shelter in the mountains

Farming the ancient way

Singing with coyotes

Singing against nuclear war -

I’ll never be tired of life.

Now I’m seventeen years old,

Very charming young man.

I sit quietly in lotus position,

Meditating, meditating for nothing.

Suddenly a voice comes to me:

“To stay young,

To save the world,

Break the mirror.”