We’ve all been there: sunlight filters through the canopy, the air smells faintly of resin and fresh leaves, and a gentle rustle of leaves accompanies the songs of birds. Instantly, the tension in our shoulders begins to melt, our mind slows, and our breathing becomes deeper. What feels like simple relaxation is, in fact, a cascade of measurable physiological and psychological benefits, something we have intuitively understood for thousands of years. Nowadays, when around 50% of the world's population lives in cities, and when many of us spend much more time indoors than outdoors, exposure to nature is something that requires conscious effort. As cities grow larger, and green spaces are being turned into parking lots and shopping malls, it is easy to forget that forests even exist, let alone that they are living, breathing spaces where we can go to look for peace and meaning.

SHINRIN-YOKU

Trust it to Japanese to have invented a word for it: shinrin-yoku, usually translated as “forest bathing,” is a modern Japanese tradition that blends ancient reverence for nature with contemporary science. It began in the 1980s, when Japan’s forestry agency encouraged people to spend unhurried time in wooded areas as an antidote to urban stress, but its roots reach back to Shinto beliefs in sacred groves and the power of living trees. Forest bathing is not hiking or exercising; it is simply the act of walking slowly, breathing deeply, and letting the forest’s sensory world — cool shade, birdsong, mossy scents, shifting light — wash over you. Japanese researchers discovered that this immersion is not just poetic, but physically measurable: time spent among trees can lower cortisol, steady the pulse, enhance mood, and improve the immune system. In Japan, many people treat shinrin-yoku almost as a preventative medicine, visiting forests the way others might visit a spa. Yet the essence of the practice is wonderfully simple: to reconnect with the living world by doing less, noticing more, and allowing the quiet company of trees to soften the mind back into balance.

patients who could see trees spent fewer post-operative days in the hospital and needed fewer pain-killing medicines than patients looking at the brick wall.

ECOPSYCHOLOGY

Ecopsychology, a term introduced in 1963 by psychology professor Robert Greenway, explores the idea that human well-being is inseparable from the health of the natural world, and that many modern psychological ailments stem from an ecological disconnection. Rather than treating the mind as an isolated, indoor phenomenon, ecopsychology treats it as something porous and responsive, shaped by landscapes, seasons, and the sensory richness of the Earth itself. Greenway argued that society’s drift toward technological enclosures — cars, offices, screens, sealed rooms — creates what he called “psychological homelessness,” a quiet but chronic estrangement from our evolutionary habitat. Ecopsychology tries to repair that rift by reinstating the natural world as an active partner in healing: time spent in wilderness, attentive walking, encounters with animals, and even simple contact with soil and plants become forms of therapy rather than hobbies. The field blends clinical psychology, anthropology, and environmental philosophy, yet its spirit remains practical: people tend to feel better, think more clearly, and behave more responsibly toward the planet when they’re immersed in non-human beauty. At its core, ecopsychology is a reminder that our minds did not arise in fluorescent-lit rooms, but in forests.

PATIENT RECOVERY

A 1984 study by Dr. Roger Ulrich, named View through a window may influence recovery from surgery, gained world-wide attention and made a huge impact on the idea that the healing power of nature is real. Dr. Ulrich tracked the recovery rates of 46 hospital patients who had undergone gall bladder operations. Half were assigned to recovery rooms facing a brick wall. The other half could see a small stand of trees outside their windows. He found that patients who could see trees spent fewer post-operative days in the hospital and needed fewer pain-killing medicines than patients looking at the brick wall. The study has been replicated in many places, with similar results.

ecopsychology is a reminder that our minds did not arise in fluorescent-lit rooms

ATTENTION RESTORATION THEORY

Environmental psychologists Stephen and Rachel Kaplan of the University of Michigan became known for their work on Attention Restoration Theory (ART), which highlights the positive psychological and cognitive impacts of having a view of nature from an office or home window. In a study named The role of nature in the context of the workplace they found that environments, including office settings, that allow views of nature are "micro-restorative settings". Brief moments of gazing at natural scenes help rest the brain's "directed attention" mechanism (the intense focus needed for work or study), thus combating mental fatigue and improving concentration.

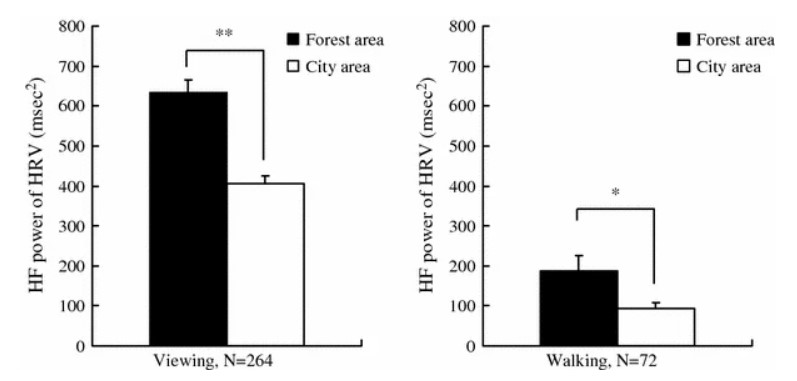

Heart rate variability, forest area vs. city area

Heart rate variability, forest area vs. city area

GROWING UP WITH TREES

Work by Andrea Faber Taylor, Frances E. Kuo and William Sullivan have uncovered a trove of amazing relationships. Their study Views of nature and self-discipline: evidence from inner city children showed the positive social effects of landscape around public housing projects. The study focused on young girls living in Chicago apartments. They found that girls in apartments with greener, more natural views scored better on tests of self-discipline than a matched group of girls with more barren views. The young ladies fortunate to have green views showed better concentration, less impulsive behavior and were better able to postpone immediate gratification. This means they can better handle things like peer pressure, sexual pressure and can generally do better in school and prepare more responsibly for later life.

Pulse rate (beats per minute), Forest area vs. City area

URBAN CRIME RATES

In another study, Environment and crime in the inner city: does vegetation reduce crime?, Drs. Kuo and Sulliwan researched the effect of vegetation on city crime. Here is what they found: Residents living in "greener" surroundings report lower levels of fear, fewer incivilities, and less aggressive and violent behavior. This study used police crime reports to examine the relationship between vegetation and crime in an inner-city neighborhood. Crime rates for 98 apartment buildings with varying levels of nearby vegetation were compared. Results indicate that although residents were randomly assigned to different levels of nearby vegetation, the greener a building's surroundings were, the fewer crimes reported. Furthermore, this pattern held for both property crimes and violent crimes. The relationship of vegetation to crime held after the number of apartments per building, building height, vacancy rate, and number of occupied units per building were accounted for.

STRESS RELIEF

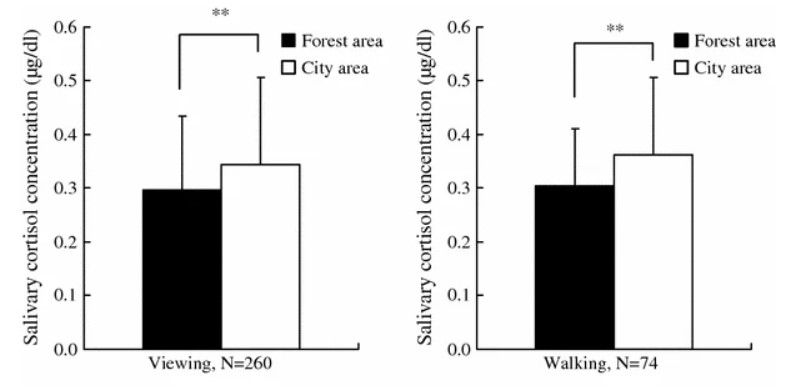

Stress is a silent killer, linked to chronic inflammation, heart disease, and weakened immunity. Yet research shows that even brief immersion in a forest can significantly reduce it. A seminal study in Japan, The physiological effects of Shinrin-yoku, measured cortisol — the body’s main stress hormone — in participants before and after walking or simply viewing a forest. Within fifteen minutes, cortisol levels dropped, heart rates slowed, and blood pressure decreased. Heart rate variability data revealed that the parasympathetic nervous system — our “rest and digest” mode — took over, signaling deep physiological relaxation.

Cortizole levels, Forest area vs. City area

Cortizole levels, Forest area vs. City area

MOOD AND EMOTIONAL WELL-BEING

The mental benefits go beyond stress reduction. Forests help restore attention and reduce mental fatigue, allowing the brain to recharge after hours of focus or urban sensory overload. Systematic reviews of forest therapy studies show that spending time among trees reduces symptoms of depression, anxiety, and anger, while enhancing vigor, pleasure, and empowerment. People report feeling calmer, more focused, and even more creative after a forest walk. Problem-solving skills, concentration, and cognitive flexibility all improve, suggesting that forests act like a natural cognitive reset button.

society’s drift toward technological enclosures — cars, offices, screens, sealed rooms — creates psychological homelessness

AIR PHARMACY

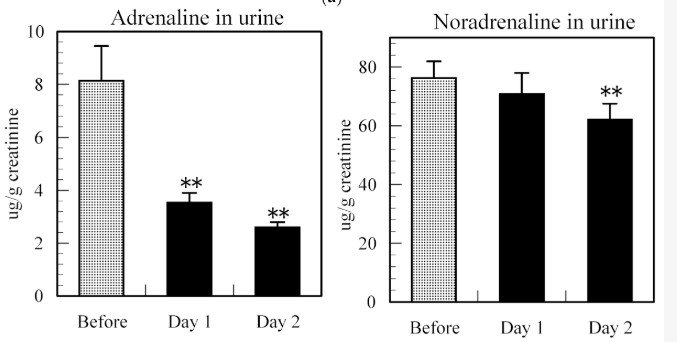

One of the most fascinating aspects of forest therapy lies in the chemicals that trees release. Trees emit volatile organic compounds called phytoncides. These include terpenes — fragrant molecules like α-pinene, limonene, and linalool — which plants produce to communicate with each other, and protect themselves from pests and infections. Even though they are invisible, forest air is full of them. For humans, inhaling these compounds appears to have anti-inflammatory, immunomodulatory, and even neuroprotective effects. Experiments show that after forest bathing, participants have increased natural killer cell activity, a key component of immune defense, which can last up to a month. (Killer cell is a type of lymphocyte which destroys infected or cancerous cells.) Inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein are reduced, and the immune system’s readiness to fight infections is heightened, as shown in the study Effect of forest bathing trips on human immune function by Dr. Qing Li. Simply breathing the air in a forest may be subtly training your immune system and reducing systemic inflammation.

Adrenaline and Noradrenaline levels after forest walks

HEART AND CIRCULATION

Another study by a group of Chinese scientists found that walking in forests also benefits the heart. Controlled trials demonstrate that forest walks lead to lower systolic and diastolic blood pressure, slower heart rates, and improved autonomic balance compared with urban environments. These effects are particularly notable in older adults with hypertension, suggesting that spending time among trees is a natural, non-drug method to support cardiovascular health.

Forest bathing is not hiking or exercising; it is simply the act of walking slowly, breathing deeply, and letting the forest’s sensory world — cool shade, birdsong, mossy scents, shifting light —wash over you.

WHERE TO BEGIN

You don’t need a retreat in a national park to start reaping the benefits. Even urban green spaces, parks with mature trees, and tree-lined streets provide measurable effects. Aim for 20–40 minutes of mindful walking, or simply sitting quietly among the trees. Notice the scents, the light filtering through leaves, the textures of bark, and the gentle sounds of nature — all of which contribute to the forest’s healing power. Forests and plants in general are more than a backdrop for leisure. They are living pharmacies, classrooms for the senses, and sanctuaries for the mind. From stress reduction and mood enhancement, to improved cognition, immunity, and heart health, to benefits for the whole community, the scientific evidence is compelling. The next time you feel tension, mental fatigue, or a low mood creeping in, step outside, find a patch of green, and let the trees do their work.