Kalmyks in Belgrade. Photo from the Politika's photo archive.

Kalmyks in Belgrade. Photo from the Politika's photo archive.

The description of the life of a social group that disintegrated decades ago and then disappeared almost without a trace is linked, no doubt, to particularly complex problems of a methodological and methodical nature. Namely, only partial reconstruction is possible, which is all the more difficult because of the modest or even non-existent primary sources (informants, archival documents, data in the press) and which relies primarily on oral traditions in the memory of external observers (1). The subjectivity of such interpretations can only be partially corrected by the use of comparative literature referring in our case to the Kalmyk culture in imperial Russia, in the Soviet Union, and in emigration. Comparative literature also helps us to bridge the gaps in the basic information network.

For the ethnological profession, the Belgrade settlement of Kalmyks, a West Mongolian people from the Volga River's lower reaches, is interesting as an example of a small community in the cosmopolitan metropolitan area, as a contribution to the ethnological appearance of Belgrade and, finally, as a fragment of Kalmyk history in emigration.

Most Kalmyks came to Yugoslavia in December 1920 with a group of 22,000 soldiers, accompanied by family members. This is the part of the Wrangl and Denikin units that were evacuated from Crimea before the penetration of the Red Army and transported to special camps near Constantinople, from where they dispersed across various European and overseas countries. There were many Don and Cuban Cossacks in this army with whom the Kalmyks lived mixed or in a close neighborhood (for example, some Cossacks adopted from the Kalmyks the Lamaistic form of Buddhism) (2). During the Russian Revolution and the Civil War, the Kalmyks, under the leadership of Russian and Cossack officers, established two regiments, the 80th Don Dzungar and the 3rd Don Kalmyk Regiment, and parts of Kalmyk cavalry were also located on the other side of the front line, in the Red Army units.

Some Kalmyks arrived in Yugoslavia in 1922, when the last anti-Bolshevik units had to withdraw from Vladivostok.

The majority of Russian immigrants in Yugoslavia lived in Belgrade. Among them were many aristocracy members, landowners, contractors, clerks, and officers; people of farmers’ origin were relatively numerous, and very few were representatives of the proletariat (3).

The fact is that, after settling in Belgrade and other European cities, poverty forced many immigrants to accept difficult physical jobs and turn into some sort of proletariat; however, they still retained "the cultural-spiritual interests and needs of their former social strata" (4).

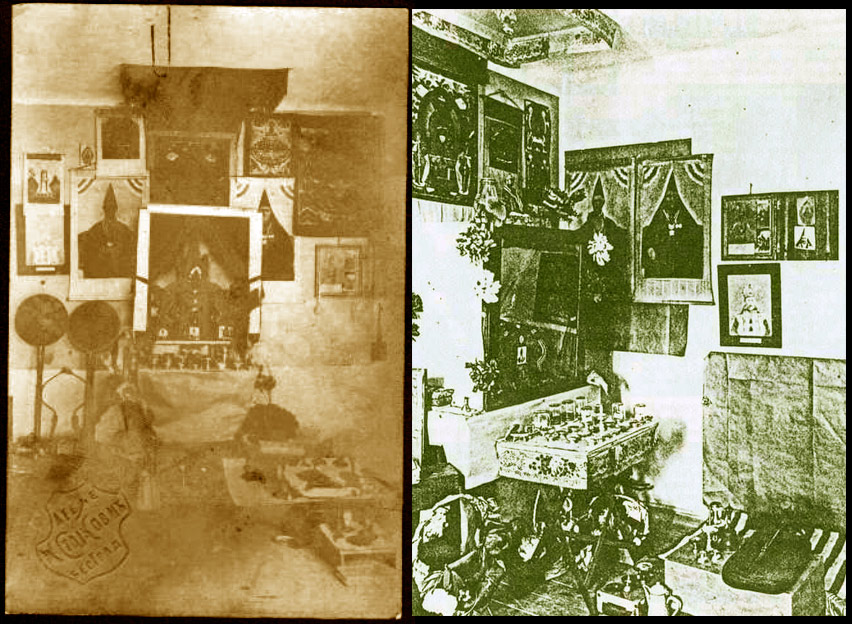

Buddhist temple in Mali Mokri Lug, Belgrade – the look of the altar in different periods.

Taking all this into consideration, the group of Kalmyk refugees, upon their arrival in Belgrade, represented the poorest class of Russian immigrants, both in material and socio-educational terms. Josip Suchy, who visited the Belgrade settlement of Kalmyks in 1932, noted that they were engaged in transportation, employed in factories and engaged in traditional local crafts as well as agriculture. There were almost no intellectuals among them, with the exception of doctors and two students at the Belgrade University (at the Faculty of Civil Engineering and the Department of Philosophy) (5). For this reason, the book by Belgrade-based Kalmyk, Dr. Erenzhen Hara-Davan, on Genghis Khan and his successors, published in Belgrade in Russian in 1929 (6), was a remarkable achievement. The work is entitled "A Cultural and Historical Description of the Mongol Empire from the 12th to the 14th Century" and is dedicated to the 700th anniversary of Genghis Khan's death. The author described the beginnings and expansion of the Mongolian state, and paid special attention to the Mongolian occupation of Russia and the Balkans and argued that it brought a number of positive consequences. The book aroused interest in international professional circles, and the author prepared a lecture on "Genghis and Mongolian penetration into Europe" (January 7, 1928) at the University of Belgrade (7).

In the first years after the Kalmyk settlement in Belgrade, an effort was made to adapt to the new environment, which was partly facilitated by the fact that all Kalmyk settlers, in addition to their Kalmyk language, also knew Russian, and thus learned Serbian faster. Those who originated in the northern foothills of the Caucasus also knew the Circassian language.

A Kalmyk leader, a Lamaist Buddhist priest, shortly after the arrival of a group of fugitives in the Yugoslav capital, asked Belgrade-based industrialist Milos Jacimovic to allow them to work at his brick mill in Mali Mokri Lug. He employed them and gave them land next to his facility. From the brick they received for free in the factory, they built 20 to 30 single-story houses and moved into them from the rented houses where they used to live. Each house was shared by two or three Kalmyk families. The living conditions were modest. Beside the houses were gardens, a common well and a common toilet. Not only those Kalmyks who worked in the brick factory, but also some of their relatives, settled in these houses.

Most Kalmyks in the beginning worked on the exctraction of clay and on its transportation to the brickyard. Over time, some of them bought themselves horses and started their own businesses; they also worked in wood, coal and similar industries. Some of them became coach drivers. Thus, in the new environment they continued the tradition of horse breeding, which they practiced on their native Don grasslands. They also did some home-made crafts.

The man was the head of the family. The Kalmyk women in Belgrade did not look for jobs, but contributed to the family budget by making slippers and fur jackets that they sold at the market (8).

The men first wore Russian military uniforms upon arrival to Belgrade (9) and later simple civilian suits that made them no different from Serbs in the surrounding area. The geographical location on the outskirts of the workers' settlement of Mali Mokri Lug proves that Belgrade's Kalmyk colony was a completely marginal community in socio-economic terms. With the gradual improvement of the economic position of individual families, their living needs increased. Thus, in the early 1930s, many Kalmyk children continued to high school education (10).

The Kalmyk community was quite closed to the outside world, linked within by their common language and origins, by the common fate of the immigrants, and by their affiliation with the Buddhist religious community. Contacts with the wider environment and Kalmyks living abroad were rare. Only the Kalmyk priests maintained links with their countrymen living in Paris, from which high religious dignitaries who occasionally participated in rituals occasionally came. They were not politically active. Although the Soviets proclaimed an amnesty for war refugees (1923), and the Kalmyk Society for Return to Homeland, headed by Bosan Kushlinov, did some propaganda, they did not choose to return to the Soviet Union.

They began to associate more freely with the Serb farmers of Mali Mokri Lug (who only knew them by the name "Chinese"). There were several mixed marriages between Serbs and Kalmyks. Kalmyk children were playing with their neighbors’ Serbian children. They also had a football pitch, the so-called "Chinese playground". They attended elementary school together.

"There have been several mixed marriages." From the Politika's photo archive.

"There have been several mixed marriages." From the Politika's photo archive.

The Kalmyk religion was Buddhism (Lamaism) with additions of Mongolian shamanism, with a pantheon of native pre-Buddhist deities and cults of historical figures (Genghis Khan, and also the imperial dynasty of the Romanovs). In 1932, there were a total of 300 Kalmyk immigrants in Belgrade, plus a few who lived in the vicinity of Pancevo, in the village of Debeljaca and in Gornji Milanovac (11). The custom of solidarity prevailed among the members of the community, which was reflected in the provision of mutual assistance and also in attending religious ceremonies and controbuting to the Kalmyk Lamaist temple.

In 1924, the high priest baksha (12) Manchu Birinov, asked and obtained official permission to arrange a tentative Buddhist shrine in a rented apartment in Mali Mokri Lug. It was a modest space, covered with carpets and decorated with several symbolic figures, with a bronze figure of the Enlightened in the background (13). Baksha Borinov, dressed in a dark blue priest's uniform, head covered with a round, gold embroidered cap, was the chief adviser to his countrymen in all life's decisions, visiting them at work and encouraging diligence and patience (14). In November 1929, the Kalmyks built a pagoda-shaped brick sanctuary, a hurul, on a piece of land donated to them by Milos Jacimovic. They built it themselves, collecting voluntary contributions (one of the donors was Princess Jelena, sister of King Alexander), and some funds were provided by the municipality. During the period between the two world wars it was the only Kalmyk sanctuary in Europe, outside the Soviet Union. At the consecration, in December 1929, the high priest, baksha Namdzlo Nimbusov of Paris and the Belgrade baksha Sango Umaldinov were present together with two gelongs (15). On the occasion of the 10th anniversary of the shrine, a solemn ceremony was held in the premises in honor of the benefactor Milos Jacimovic. On this occasion, the Kalmyks presented him with a thank-you note written in a beautiful script, which his grandson later donated to the Belgrade City Museum. After the ceremony, the guests were offered tea and cakes in the next room. When Jacimovic died in 1940, Kalmyks also attended his funeral ceremony.

The tradition of wooden buildings was present in the architecture of the Kalmyk temples, and since the late 18th century they were also built of brick and stone. The main temple usually had a large central room with a vaulted tower, richly decorated with carvings, murals, paintings and bronze sculptures (16). The Kalmyks had their religious center near Astrakhan (Kalmyk Bazaar), in today’s Russia. This is where the Great Llama lived before the October Revolution. The wooden building of the main shrine in the area had an interior decorated with silk paintings (17). In addition to the larger permanent temples, they also had mobile smaller shrines in their yurts (18).

Compared to the temple compounds usually built by the Mongols and Kalmyks, the Belgrade Buddhist temple was small and modest. It was built in the form of a pagoda with three slightly upturned roof edges (one of the basic types of Mongolian shrines, where Chinese architectural influence is seen). It was standing in a fenced yard, surrounded by fruit trees. Next to the shrine was an added building with rooms for priests and a classroom where Kalmyk, Russian and Serbian languages were taught.

Classroom at the Kalmyk Buddhist Temple in Belgrade. The title reads: "A school that works once a week, has two subjects, and doesn't punish students for skipping classes".

From the roof corners of the Belgrade pagoda hung metal bells (protection from demons) that chimed in the wind. A lamaistic symbol was attached to the top of the roof – the vajra. (19) Above the front door, on the front of the building, was a Buddhist symbol: two gazelles and between them, on a lotus flower, a wheel of Buddha's teaching with eight parts. There was only one window on the ground floor, and four openings on each of the two upper floors.

Vajra is a Buddhist symbol of a lightning strike, invincible truths or absolutes, an attribute of Tibetan deities, and a ritual object during Lamaist rites.

The Kalmyks apparently brought the sanctuary equipment with them from Russia. Across from the entrance, in the lodge, was an altar on which, in addition to two Buddha statues, there were religious objects and relics, and beneath them were bowls of sacrificial gifts. To the left of the altar, in front of the windows, were two low tables, seats for two Lamaist monks and shelves for storing religious texts. On the walls were traditional religious paintings, tankas, and photographs of religious dignitaries. The floor was made of ordinary wooden boards, covered with cheap, factory-made carpets. The high ceiling was supported by four wooden, vividly painted pillars with Buddhist symbols (the wheel of Buddha's teaching, a lotus flower, etc.). Buddhist flags (white, red, yellow, blue, green) hung from the ceiling.

On the tables of both priests were laid out lamaistic ritual objects: rosary with 54 beads, ochira (double vajra), cymbals, sacred records in Tibetan, a rope for contact between the believers and the priests, a bowl with various grains and seeds, a bowl with water, a bowl with a peacock feather (boom pa), incense and scents.

Buddhist temple in Belgrade, exterior and interior. Photo by Dr. H. Klar.

A brief but valuable description of the interior of the sanctuary was published by Josip Suchy during his visit to the Belgrade Kalmyks in 1932. His report shows that the equipment has been somewhat modified and supplemented over time.

"There is a pleasant shade in the Buddhist temple. The windows are covered with beautiful curtains so that it is quite dark in the sanctuary. From the ceiling hangs an electric light bulb and a large glass ball. In the middle of the temple, against the wall, is an altar on which the Buddha himself sits in an oriental manner. Above him, two Buddhist saints reign, the first of whom is a former Buddhist chief, called the Bakshama Lama. On the altar are gifts from Buddhist believers. Just today (mid-July) they celebrated with a great feast and the believers bestowed on Buddha what they could in their misery. Some of them rice, others sweets and cakes... I also saw a ten-dinar coin on the altar... There are pictures of other high priests and prophets of the Buddhist faith hanging on the sides. On the right side of the altar there are mattresses on which gelong sits during a religious rite lasting at least three to four hours. "(20)

Buddhist temple in Belgrade - the interior. From the Politika's photo archive.

Buddhist temple in Belgrade - the interior. From the Politika's photo archive.

Suchy also took a photo of the exterior of the shrine. During the major holidays, the Kalmyks of Belgrade set up a table in the sanctuary's garden, covered it with donated food and beverages, drank tea mixed with butter, milk and salt, and feasted on horse meat, according to some reports. In the new environment, some holiday customs were lost or altered. For example, of the three traditional men's competitions: running, archery and wrestling - only the last one was preserved.

Lamaist priests who lived in celibacy and obeyed the other commandments of monastic life were the undisputed leaders of the Kalmyk settlement in Belgrade. And otherwise they enjoyed a greater reputation than people who lived a worldly life. Most Kalmyk lamas were descended from pastoral families, and only the highest lamas usually belonged to the aristocracy. They knew the language of the scriptures – Tibetan and Old Mongolian, and were proficient in Tibetan medicine and astrology. As members of the gelugp sect, they recognized as their highest religious leader the Tibetan Dalai Lama. In him they saw the incarnation of the bodhisattva of Avalokiteshvara.

The Kalmyk clergy supervised the life of each family and participated in all aspects of their lives (for example, the gelong chose names for babies, determined the wedding day, treated the sick, performed funeral rites) (21). This also applied to the Kalmyk colony in Belgrade.

Believers attended Lamaist rites for several hours, expecting spiritual purification and "salvation" in the next reincarnations. It was about the well-being of the visitor as well as the whole community. In addition to the daily service, their religious calendar also included significant dates from the Buddha's life, such as the Full Moon Feast, the New Moon Feast, the Tibetan New Year, and others (22).

During World War II, some Kalmyks of Belgrade left and became German soldiers on the Eastern Front. The Germans promised to establish a "free Kalmyk state" somewhere in the occupied territory of the Soviet Union. They also urged civilian expatriates to organize their own government.

Kalmyk Buddhist Temple in Belgrade, now inexistent.

In the fierce fighting for the liberation of Belgrade, which took place in the immediate vicinity of Mali Mokri Lug from October 12 to 16, 1944, the upper part of the tower of the Kalmyk shrine was partially destroyed. Even before that, a part of Kalmyk community had gone to Germany, and after German defeat they were deployed to camps run by US charities. Thus, with a group of Kalmyks, the Belgrade's high priest (baksh) Umaldinov and his associates, Helonzi Menjkov and Ignatov, also arrived to Germany. They probably brought with them the interior equipment of the Belgrade temple. Baksh Umaldinov, who was already an old man, died in 1946 in Krumbach, Bavaria. Those Kalmyks who remained in Yugoslavia were mostly deported to the Soviet Union after the war (and subsequently to Siberia, where the Kalmyks from the Soviet Union had been deported in 1943). (23). The Kalmyk colony in Belgrade thus completely disappeared.

Other tenants have moved into the houses on what used to be Buddhist Street, later called Budva Street. In 1948 the tower of the temple was demolished, and the building was transformed into a Cultural Center, where meetings, dances and weddings were organized. Later, in that same building, the local municipality had its premises, and then it was taken over and partly renovated by the company Buducnost (Future), to be used as their refrigeration facility.

Kalmyk refugees (800 people, including some of the Belgrade Kalmyks) lived in detention camps near Munich until the winter of 1951-1952, when 200-250 Kalmyk families moved to the United States under the patronage of the US Church World Service and The Tolstoy Foundation (in total around 650 people). They were later joined by their countrymen from France, so in 1980 the Kalmyk community in the USA numbered about 300 families, with approximately 900 people. They were settled mainly in the US states of Pennsylvania and New Jersey (24).

—

Retrieved from: Traditiones, Acta Institutes Ethnographic Slovenorum, iss. 17, 1988. Published in Journal of Culture of the East no. 25, YU ISSN 0352-4019, July-September 1990. Translated from Slovenian to Serbo-Croatian by Tatjana Latinović. English translation: The Travel Club.

—

Footnotes:

1. Among the informants, we are most grateful to Mara Stevanovic, Lomina 57, Belgrade.

2. Helmut von Glasenapp, Der Buddhismus in Indien und im Fernen Osten, Berlin-Zurich 1935, p. 347.

3. Nikolai Fedorov, "Russian Emigration", Croatian Review, 1939, no. 7-8, pp. 373. Aleksije Jelacic, "Russian Emigration in Yugoslavia", New Europe, 1930, no. 4, p. 242.

4. N. Fedorov, n.d., p. 372.

5. Joseph Suchy, "Visiting Buddhists," Morning, 1932, no. 1971, p. 5.

6. Dr. Eugene Hara-Davan, Chingis-Han as a Commander and His Inheritance, Author's Edition, Belgrade 1929, ch. i: Irena Griekat-Radulović, "Kalmici in Belgrade", Politika September 13, 1985, p. 12.

7. They included the book in their bibliography e.g. Ralph Fox (Gengis Khan, Hamburg-Paris-Bologna 1936) and Reinhold Neumann Hodizz (Dschingis Khan, Reinbek bei Hamburg, 1985).

8. Slavoljub Kacarevic, Where did the "Chinese Pagoda" disappear?, Politika, September 8, 1985, p. 12.

9. Zeitschrift fur Buddhismus 1924/25, Munich 1925, no. 2, p. 388.

10. Suchy, at nav. site.

11. Ibid.

12. Baksa - Senior Lama, "Faith Master", who helps people with advice.

13. Gl. whop. 9.

14. Right there.

15. Belgrade Guide, Belgrade, 1920. Gelong (Tibet. DGe-slong) - an ordained monk, who completed a 12-year education under the guidance of an elder Lamaist monk.

16. The Bolshevik Soviet Encyclopedia, Vol. 11, Moscow, 1973 (3rd ed., Pp. 223-224).

17. Glasenapp, n.d. p. 347.

18. Drawing of the Kalmyk Shrine in the Yurt, by R. Karutz, Die Volker Nord - und Mittel - Asiens, Stuttgart, 1925, p. 69.

19. Vajra (Tibet. RDo-rje) - symbol of lightning, invincible truth or absolute. The attribute of Tibetan deities and ritual object during Lamaist rites.

20. Suchy, at nav. site.

21. Kalmici, c. Naroy of Peace, Peoples of the European Honor of the USSR II, Moscow, 1964, p. 745.

22. Giuseppe Tucci.Walther Heissig, Die religionen Tibets und der Mongolei, Die Religionen der Menschheit, Bd. 20, Stuttgart-Berlin-Cologne-Mainz 1970, p. 166-167.

23. Koldong Sodnom, The Destiny of the Don Kalmyks, Them Very Clergy, Author's Edition, USA 1984, p. 150.

24. Arash Bormashinov, Kalmyks, v. Harvard Encyclopedia of American Ethnic Groups, Harvard University Press, Cambridge and London 1980, p. 599.