PHOTOGRAPHY BY: AMY WESTON

PHOTOGRAPHY BY: AMY WESTON

On the evening of August 8th, which was the third day of street fighting in the London suburb of Croydon, the protesting kids set fire to some buildings including a furniture shop called Reeves which had been there for several generations. From the pictures on the TV screen I thought I recognised it. In the late 1930's my mother used to go once a week to Croydon to shop and I often accompanied her. I could help her carry things and if there were two of us we could turn it into an outing, which meant going to the cinema for the early afternoon showing. We went first to Surrey Street market, then to a large department store, not so far from the furniture shop, and finally and triumphantly to the Odeon Cinema which was almost next door. Each time we watched, and afterwards commented on, a new Hollywood release. Thanks to my mother and these films I began at the age of ten or eleven to learn a little about storytelling. (Ah! Howard Hawks, Capra, Dieterle, Archie Mayo....)

On August 8th the kids were rioting because they had no future, no words and nowhere to go. One of them, arrested for looting, was eleven years old. Watching the pictures of the Croydon riots I wanted to share my reactions with my mother, long since dead, but she wasn't available, and I knew this was because I couldn't remember the name of the Department store where we regularly went before hurrying to the cinema. I searched persistently for the name and couldn't find it. Suddenly it came to me: Kennards. Kennards! Straightaway my mother was there, looking with me at the footage of the Croydon riots. Looting is consumerism stood on its head with empty pockets.

Strange how names – even a distant one like Kennards – can be so intimately attached to a personal physical presence; such names operate like passwords.

The lake surrounded by mountains is very deep and about 70 km long. The Rhone flows through it. In stormy weather the waves look like those of a sea. Among the fish that breed here is the Arctic Charr – much acclaimed by gourmets. The Charr belongs to the Salmon family. When small it is almost transparent like a blueish silk handkerchief; when large it can weigh 15 kg. As their spawning season approaches, the ventral sides and pectoral fins of the adult males turn an orange-red.

On the southern side of the lake is a town on a hill, and between the hill and lakeside there is space for a small harbour, a promenade with cafés, a swimming pool, a narrow shingle beach, playgrounds, grass banks and palm trees, and on summer days in August these add up to something like a miniature and modest seaside resort.

Those who gather there are on vacation. They have left their everyday lives behind somewhere. Maybe a few kilometres away, maybe hundreds. They have emptied themselves. The etymological root of the word vacation is the Latin vacare, to be empty, to be free.

If you walk there, you have to pick your way – for the space is narrow and very small – between their mostly reclining freedoms. Many of the women and men on vacation are between thirty and fifty. Barefoot, barelegged, lying on towels in the sun or in the shade of trees, some of them swimming with children, others lounging in chairs. No big projects, for the place is too small and their time here too short. (It's like this that the hours lengthen.) No deadlines. Few words. The world and its vocabulary, which they normally repeat but don't believe in, have been left behind. To be empty, free. Doing nothing.

Yet not quite. Little blessings arrive which they collect. For the most part these blessings are memories yet it is misleading to say this, for, at the same time, they are promises. They collect the remembered pleasures of promises which cannot apply to the future which they have gladly vacated , but somehow do apply to the brief, empty present.

The promises are wordless and physical. Some can be seen, some can be touched, some can be heard, some can be tasted. Some are no more than messages in the pulse.

The taste of chocolate. The width of her hips. The splashing of water. The length of the daughter's drenched hair. The way he laughed early this morning. The gulls above the boat. The crow's feet by the corners of her eyes. The tattoo he made such a row about. The dog with its tongue hanging out in the heat. The promises in such things operate as passwords: passwords towards a previous expectancy about life. And the holidaymakers on the lakeside collect these passwords, finger them, whisper them, and are wordlessly reminded of that expectancy, which they live again surreptitiously.

Very little or nothing in the lives so far lived by the kids in Croydon has confirmed or encouraged any such expectancy. And so they live, isolated but together, in the desperately violent present.

—

Text originally published on www.opendemocracy.net.

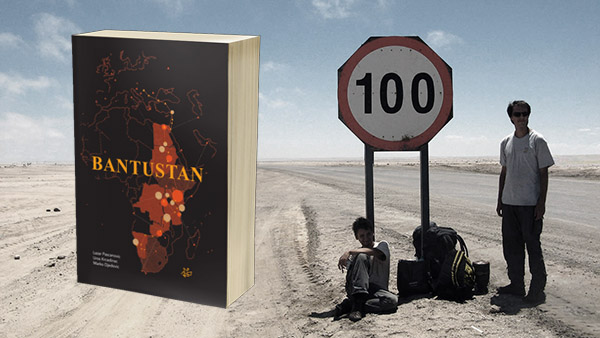

Iconic photo of disorder in Croydon, author of which is Amy Weston (agency WENN), doesn't show protesters, police and usual violence, but rather a tragedy of a Polish emigrant, Monika Konczyik, five months after moving to Britain.