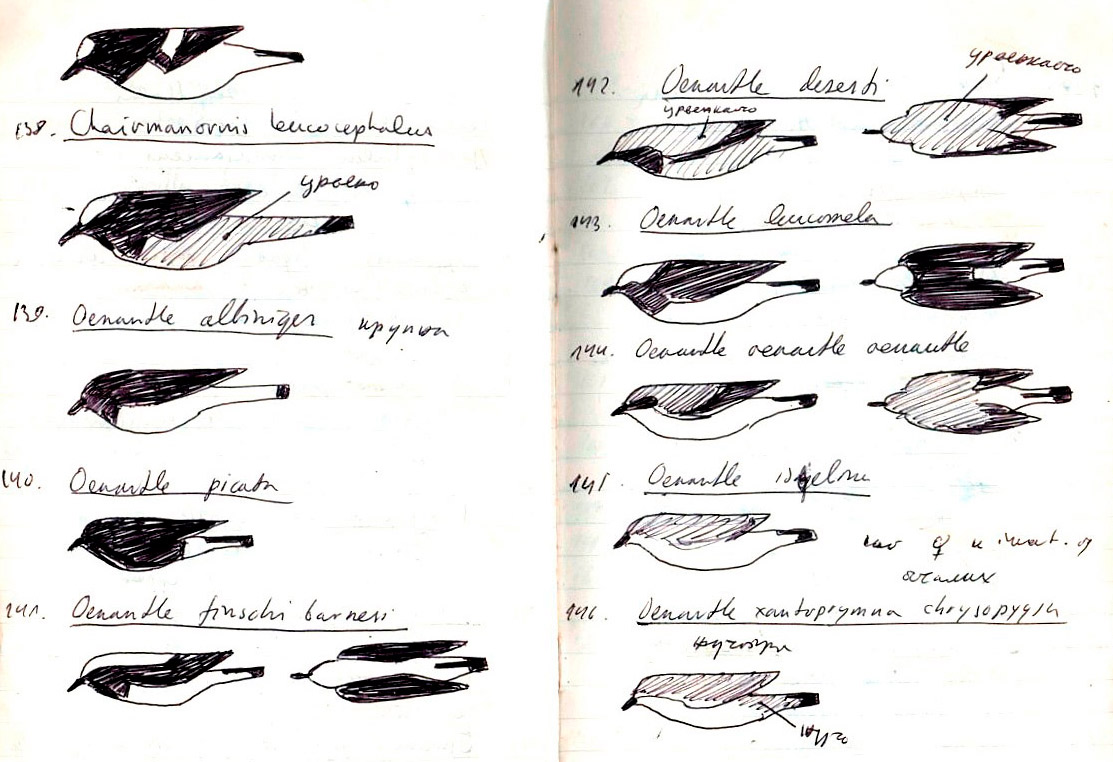

Wheateaters (from my gray notebook).

Wheateaters (from my gray notebook).

I was recently approached by the Afghanistan Analysts Network from Kabul (AAN for short). The occasion was the news that Czech zoologist Daniel Jablonski decided to examine the forgotten collection of reptiles and amphibians from Afghanistan, kept at the Belgrade Institute for Biological Research – a collection that had spent decades collecting dust. Jablonski was surprised when, going through the collection, he found specimens unknown to the professional public that still represent a significant contribution to science, such as the northernmost find of the yellow-bellied skink (Eurylepis taeniolata). As he himself admits, Afghanistan is the center of biodiversity of certain groups of amphibians and reptiles. And immediately, in May 2019, together with three Serbian authors, he published his findings about the collection in a scientific journal.

Since none of the authors of that scientific paper had ever been to Afghanistan – not even Jablonski, who is a specialist in amphibians and reptiles of Central Asia – the AAN analyst Jelena Bjelica couldn’t help but wonder who actually went there. Who went to Afghanistan back in 1972, hunted down those unfortunate beasts in the God-forsaken deserts and mountains, put them in alcohol, dragged them in jars all around Afghanistan for months and finally brought them to Belgrade.

That’s how she found me. And she wanted the whole story.

Her article "Lizards of Afghanistan: An unknown collection discovered in Serbia”, published on July 30, 2019, says that I introduced myself to her as a then young bird researcher and "an adventurer who had travel in his blood." I told her that the bird map of Afghanistan had been full of blank spaces, and I had wanted to fill those spaces.

Her article further relates how, lugging my backpack, I took a bus from Belgrade to Istanbul, and from there, all the way by land, to Tehran. Finally on July 26, 1972 I entered Afghanistan near the Fortress of Islam (Islam Qala), in the province of Herat.

Indeed, in ten days I had traveled 5,000 kilometers, passing by Ararat, stopping along the way in Tehran and other places, and seeing Mt. Elbrus from the bus window. But all that was nothing compared to what still awaited me on that formative journey of my youth.

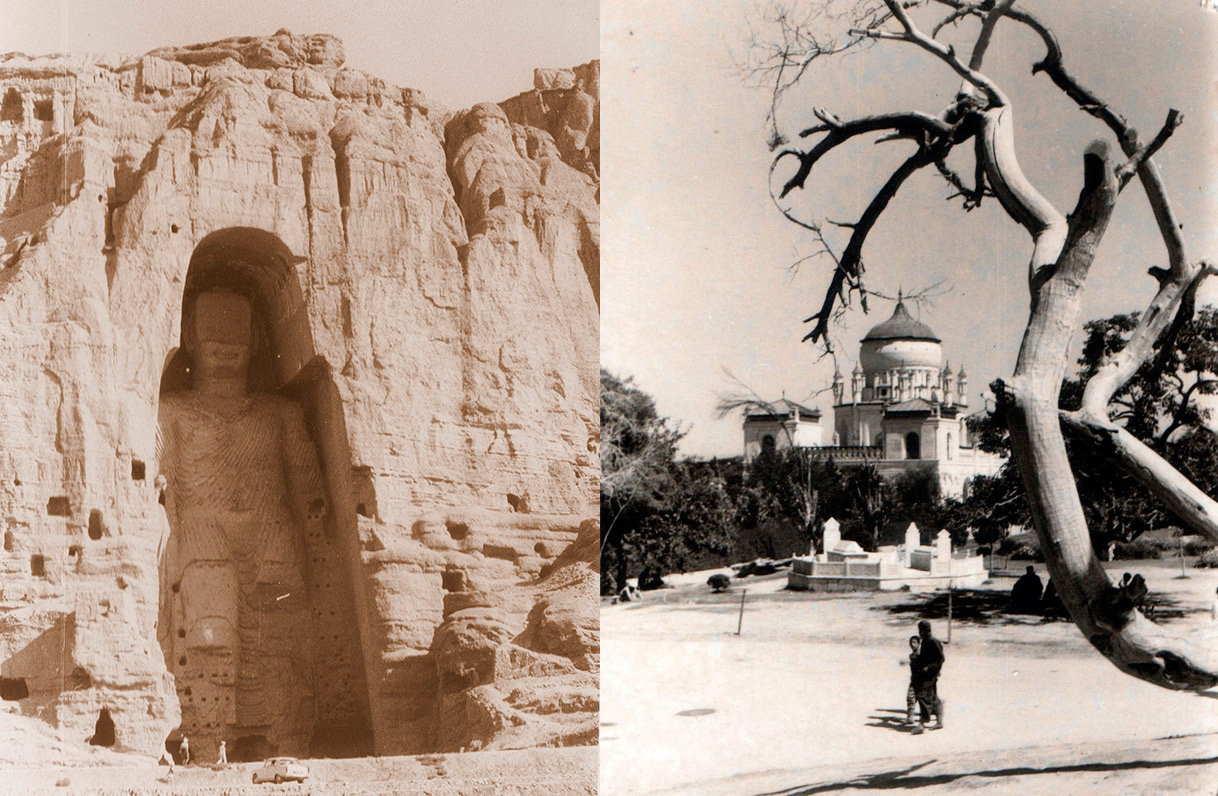

Left: Buddha of Bamiyan, which is no longer there. Right: Kabul.

As I happened to be in Kabul on August 19, Afghanistan's Independence Day, I had the opportunity to observe a military parade, the last to be attended by Mohammad Zahir Shah as a monarch. I had no idea that a coup and the overthrow of the ruler was already brewing. In retrospect, now it seems that the Shah and I were the only two people in Afghanistan who didn’t see it coming.

With the AAN 's recent interest in my journey, memories started rushing back. I felt the urge to talk about my almost forgotten travels in Afghanistan in the summer of 1972. To describe the journey of a twenty-seven-year-old naturalist from Belgrade, a completely private and non-hippie venture quite unusual in the times of Tito's Yugoslavia.

My choice of destination at that time was greatly influenced by the publication of a most extraordinary book on the birds of the Near and Middle East (Les Oiseaux du Proche et du Moyen Orient, Paris 1970) by two famous French researchers named François Hüe and Robert Daniel Etchécopar, with incredible illustrations by Paul Barruel. By the Middle East they also meant Afghanistan.

Of course, that was not all. Given my classical education, the idea of visiting an under-explored country with a rich cultural history was irresistible to me. Especially the land where, like a strange constellation, a handful of Alexander's Alexandrias were scattered towards the east... Also, the very prospect that I would find myself in the presence of Greco-Buddhist monuments for the first time in my life greatly fed my enthusiasm.

As for my decision to embark on a rather uncertain naturalistic research in a distant and unknown country, it should be said that at that time I had just completed my compulsory one-year military training in the Yugoslav National Army, and felt that I possessed enough strength and self-confidence for the greatest journey of my life.

At that time I was passionately interested in zoogeography, so I thought that a trip from the Bosphorus to the heart of Asia would give me a great opportunity to get to know and truly understand the ecosystems of the steppe and the desert. Until then, I had only encountered its meager, modified fragments on the Balkan Peninsula. In addition, although in my field and mountaineering experience I had conquered almost all off the highest mountain peaks in Yugoslavia, my height record was Mt. Triglav in Slovenia, with an insignificant altitude of 2,864 meters. But out there in Afghanistan, Mt. Hindu Kush was waiting for me, with an average height of 4,500 meters! And I didn't ask myself why the famous traveler Ibn Battuta had called that powerful mountain the Slayer of the Hindus.

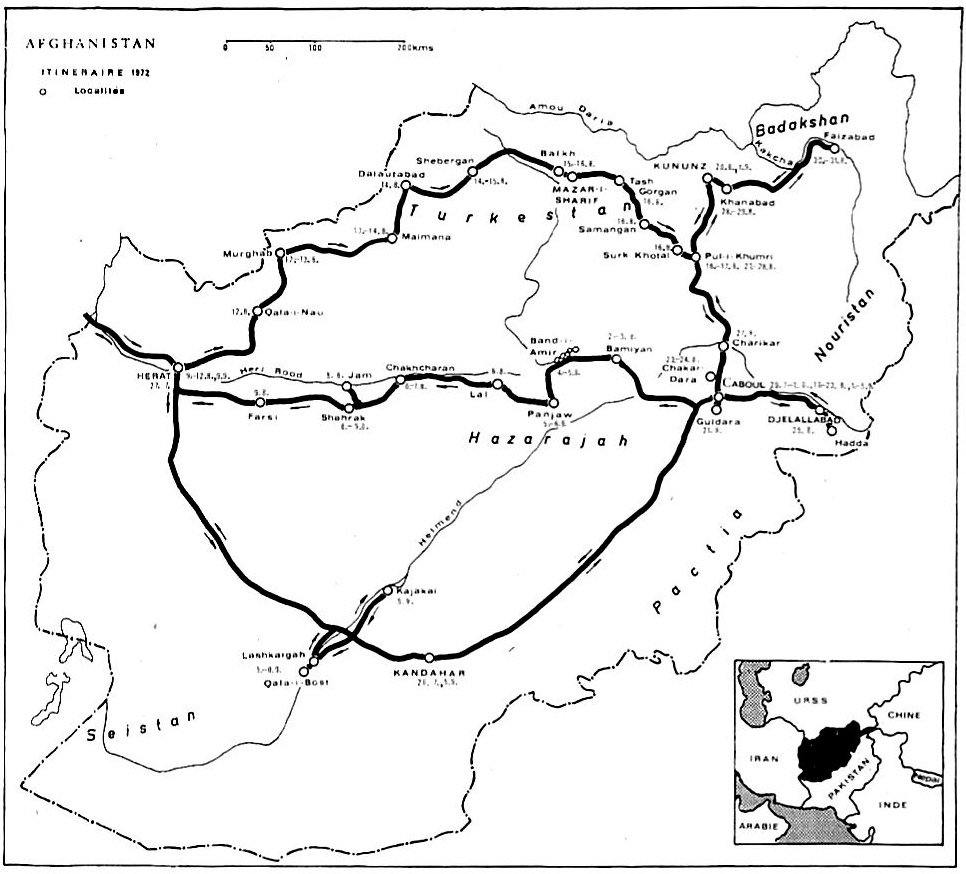

My Afghanistan travel itinerary

Of my many ornithological “great expectations”, I will only mention three. The third on my list was my desire to see some spectacular birds of prey, most notably the bearded vulture (Gypaetus barbatus), which I had seen in Yugoslavia only once before, in Macedonia. In general, about fifty years ago, large raptors had already become a rarity in most of Europe. Also, other types of eagles and falcons that I had never seen before were waiting for me in Afghanistan. That's why in one of the two field notebooks I carried, the gray one, I carefully made notes and drew pictures that would later help me identify the yet unseen species of birds of prey in the sky.

And I was not disappointed: throughout Afghanistan, the bearded vulture was the most common species of vulture after the Egyptian vulture (Neophron percnopterus), especially in the central mountainous areas, where I saw it every day. It was somewhat rarer in the lower parts. By the way, the bearded vulture is an amazing, huge bird that feeds almost exclusively on marrow-filled bones. Bones previously gnawed by jackals and feathered vultures.

The most numerous scavenger was the Egyptian vulture, especially around villages and nomadic camps, because it feeds on the worst kinds of waste. Once, in the Ajda Valley (Darya e Ajdahar), two men suddenly appeared in front of me with rifles and a freshly killed Egyptian vulture, offering to sell it to me. With their facial expressions and gestures, they explained that it tastes great when cooked. I immediately remembered that street children followed me and every other foreigner in Kabul shouting "Mister Kachalu, Mister Kachalu!" (Mr. Potato, Mr. Potato!). Accordingly, I believe that these two vulture killers also thought that foreigners were complete ignoramuses and fools worth deceiving in any way. That has not changed even to this day: more recently, I hear that seagulls have been offered for sale in Kabul as wild ducks.

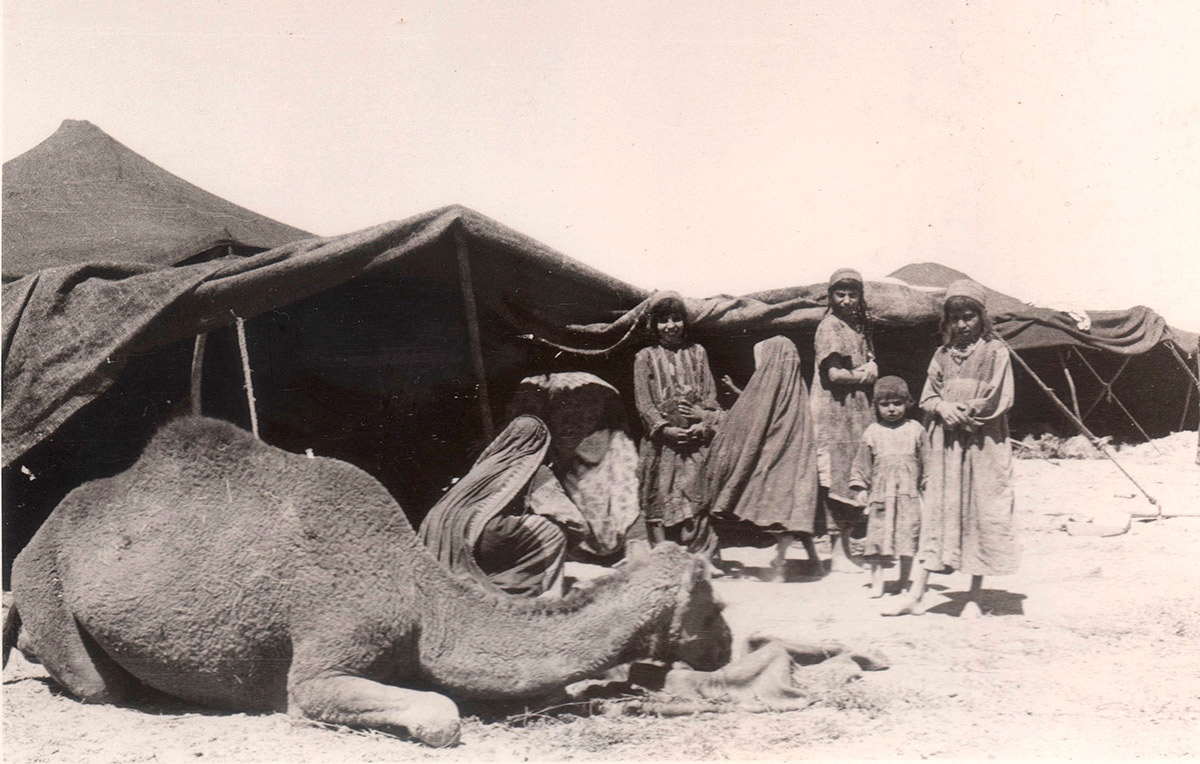

A nomad camp in Afghanistan

My second great wish was to get to know the numerous species of wheateaters (genus Oenanthe), desert-steppe birds with white tails. Central Asia is, in all likelihood, the center of biodiversity of this genus, of which there were only two species in Yugoslavia. Each of the species is very slightly different from at least one other similar species, and it is especially difficult to identify females and young individuals in transitional seasonal plumage. Which is exactly what I feared, as they changed plumage in July and August. Keep in mind that, back in 1972, there were no pocket guidebooks for identification, with illustrations of the birds of Afghanistan or the region. My eagerness to find some extremely interesting species of wheateaters was thus coupled with some very serious problems of their reliable identification.

That's why, as soon as I arrived in Kabul from Herat, I went to the Kabul Zoo, that had a small Zoological Museum. It was founded by the German zoologist Jochen Nittamer, the son of the equally or even more famous Günter Nittamer, curator-zoologist of the Berlin, Bonn and Vienna natural history museums. Nittamer Junior had spent 1964-1966 in Kabul as part of Bonn’s collaboration with Kabul University, and studied mammals and birds of Afghanistan. That was when a collection of birds was created there, the specimens of which were identified by Nittamer Jr. himself.

In 1972, the zoo and museum were curated by two other German zoologists, Günter Noge, an assistant professor at Kabul University and later a long-time director of the Cologne Zoo, and M. Boeckler (I don’t know anything about him), to whom I had previously introduced myself in a letter. They welcomed me kindly and allowed me to examine the whole collection of birds in detail, as well as to use their library.

For two weeks, I studied the stuffed birds of Afghanistan learning how to identify them, alive, in the field. I recorded all of this in my gray notebook, which was always in my pocket. I was kept company by an orphaned child chimpanzee who, while I was studying birds, sat on my lap, holding me in the embrace of his long arms. Thanks to my self-training at the Kabul Zoo and Museum during July and August 1972, as well as the notes and drawings I made there, I was later able to identify as many as eight different species of wheateater in the field. And I have seen them in at least twenty different variations and stages.

Finally, at the very top of my Afghanistan bird bucket list, was my wish to see the Afghan snowfinch (Pyrgilauda theresae), an endemic bird species. It should be said right away that birds easily fly long distances, so compared to other animals and plants, endemic species are relatively rare, such as birds whose total distribution is within the borders of one country. After all, it is the only endemic Afghan bird species. The case is quite different with land birds of oceanic island states where, due to isolation, endemic bird species are much more common. But Afghanistan is the place where biodiversity was born. Besides, isn't the Hindu Kush, the only homeland of the Afghan snowfinch, an isolated high-mountain island in its own right?

The Afghan snowfinch is a grayish-brown mountain songbird that lives in a zone of about 3,000 meters above sea level. It is very similar to the previously known white-winged snowfinch (Montifringilla nivalis), which lives in the summer snow zone of the high mountains in the south of Europe (Pyrenees, Alps, Apennines, Balkan mountains), but also in Afghanistan.

Perhaps a better, more suitable name for the species would be Afghan undeground finch, because the most striking feature of this bird is that it nests in rodent burrows, most commonly that of ground squirrels. Since it builds its nest from hair and feathers deep at the farthest end of the tunnel, we can really consider it a subterranean bird.

Science discovered the Afghan snowfinch relatively late. It was first recorded in 1937, on the Shibar pass between Kabul and Bamiyan, and described under the name Montifringilla theresae in the same year by British Colonel Richard Meinertzhagen (1878–1967). Meinertzhagen was a controversial mix of boastful soldier, skilled spy, adventurer and ornithologist; such combinations are not that uncommon among ornithologists.

At that time, half a cenutry ago, I regarded Meinertzhagen as one of the greatest British ornithologists, who found many new species and subspecies on expeditions to various continents around the world. It has since been proven that he was in fact a fraud, a writer of false diaries and reports, a forger of documents and a thief of stuffed birds from other people's collections. One by one, his false scientific discoveries were exposed. There is only one left that has been verified to be authentic – and it is precisely our Afghan, endemic, underground Theresa’s finch.

But who is Theresa? Theresa Clay (Theresa Rachel Clay, 1911–1995) was a zoologist (but also a member of MI5 during the Second World War) and a thirty year junior cousin of Meinertzhagen's – they had common ancestors in the second generation. She became his favorite, as well as his goddaughter, at the age of fifteen, and after the mysterious death of his second wife she also became his housekeeper, caregiver, collaborator, secretary, confidant and inseparable companion. "Uncle" and godfather Meinertzhagen dedicated many of his false ornithological discoveries to Theresa – but also his only real discovery.

I managed to see the endemic Theresa's finch in several places in the foothills of the Hindu Kush. When on August 8, 1972 I also found it on Sia Koh, a 3,000-meter high mountain pass between Sharak and Jam, it was the then new, unknown westernmost point of its distribution. There was no end to my happiness. As a young man, I believed that with that discovery I had done a great thing for Afghanistan, and for world ornithology.

All the birds I saw and observed in Afghanistan that summer, I recorded in the second, red notebook of my field diary. After that I published an article in French in the international ornithological journal Alauda (Latin for “Lark”). The chief editor at that time was my slightly older friend, the French ornithologist Jacques Vieillard. Like so many explorers, he died of malaria, while hanging around the tropics in Brazil in 2010. Vieillard also had firsthand experience with the birds of Afghanistan, as did some other French and German explorers of that era. Back then, the English language was not as dominant in science as it is today, which is why I chose to have my article published in French. However, now I see that my paper Observations ornithologiques en Afghanistan is almost forgotten, and that today's authors quote almost exclusively from sources in English.

Thanks to my recent contact with analysts from Kabul (Afghanistan Analysts Network), many memories from that trip came back to me in their full splendor. And I took a look at my diaries, my two precious notebooks. I found out which was the first bird that had caught my attention: already on my first day, in Herat, on the western border of Afghanistan, I was enchanted by the mynas (Acridotheres tristis) – lively, colorful, noisy and curious birds from the starling family. I had never seen them in real life before. Mynas originally dwell in the Middle East, but nowadays they have spread invasively throughout the subtropical and tropical belt of other parts of the world.

During July and August, I managed to travel across most of Afghanistan and to observe and record birds everywhere, but also to catch some reptiles and amphibians for my herpetologist colleague who stayed in Belgrade. I also trekked many desert and mountain trails that none of the earlier explorers-naturalists had traversed, not even my predecessor and role model, Knud Paludan from Danmark.

In all likelihood, no ornithologist before me had passed the great Black Mountain (Sia Koh). None had explored the surroundings of the marvelous Jam Minaret, nor visited the valley of the Hari Rod River upstream of the village of Farsi. By bus, truck, taxi, jeep, as well as by bicycle, horse and camel, I passed almost all parts of Afghanistan, with the exception of Wahan and Nuristan, which were forbidden border zones at that time. In the Yugoslav embassy in Kabul, they had warned me that many parts of Afghanistan were not safe at all, and advised me to give up some remote stages of my planned itinerary. But when you are 27, warnings are easily disregarded.

Staying in Afghanistan and moving along busy roads, but also those less traveled, I could not help but notice, as well as in the neighboring Iran, the conspicuous presence of armed soldiers, that is, the army as well as the police. This fit in with my general impression that the government was struggling to keep control of the country.

Also, everywhere outside the cities, I met groups of civilians wearing turbans, not only armed, but also proudly decorated with bandoleers with rows of bullets crossed on their chest. I noticed that, since the traditional costume did not include any belt over the shirt, revolvers and pistols were carried hanging on a strap diagonally across the left shoulder.

What I didn't expect, and most definitely did not like, was how they sometimes treated a foreigner and a traveler. I found one gesture particularly creepy (especially when it was addressed to me instead of a “hello”): a gesture which consisted of two connected movements of the palm across the throat accompanied by a look of hatred, rolled eyes and a toothy smile: (1) slitting the throat with the edge of the hand and (2) a sudden movement of the fist outstretched upwards, meaning something like "there goes your head!" After some time, I stopped paying attention to that, but I didn’t like the feeling that the Afghans obviously didn’t trust me.

In that relatively peaceful time, in the non-aligned Afghanistan, the influences of the great powers were visible to the naked eye. In Kabul and in the north of the country, along the border with the USSR, the streets were dominated by GAZ-24 Volga cars, while in the south, especially around the American hydroelectric power plant construction sites on the Helmand River, large General Motors vehicles prevailed.

From Lashkar Gah to Kajaki, where the Americans built the Kajaki Dam, which was later celebrated in the film, I was given a lift by a teacher in the role of a taxi driver in his huge 1960 Chevrolet. He charged me 1,500 Afghans – about 20 USD then, or around 40 in today’s money. It was an extremely expensive ride, both for that time and for my budget. On that occasion, the teacher boasted to me that he is a serdar, a tribal leader. At the beginning of our ride, he stopped by his house and picked up three of his cousins, just in case. They all sat in the front, next to the driver. I sat in the back. That trip brought me, among other things, my first encounter with the most beautiful of swallows – the wire-tailed swallows (Hirundo smithii) that chased insects above the waters of the Helmand River, bobbing above the surface like large and colorful water lilies.

Azdar Dare

Finally, I also remember the great and faithful driver-mechanic-interpreter Matin, who drove a Toyota Land Cruiser jeep rented from Hertz in Kabul for three weeks. He found what I was doing very strange and inexplicable, unable to understand why I was exposing myself to such risks, costs and efforts. At first, he was a little shy of me and kept a watchful eye on my every move.

At one point, somewhere in the middle of a mountaneous desert, I was trying to catch a very timid lizard. I was hiding behind rocks, slowly creeping towards the animal. Being focused on my prey, I was completely unaware that the planned trajectory of my attack on the lizard was passing right by Matin, who was standing in the shade, leaning on a rock. However, he saw me and mistakenly concluded that I was sneaking up on him. Of course, he hadn't even noticed the lizard. He must have remembered some of our disputes from that same morning, about which road we should take, and thought that I was trying to attack him.

Judging that the hapless lizard was now within reach, I rushed at it with all my might. Poor Matin understood that his darkest suspicions had come true, so he leapt and began to run away from me, screaming and wailing. When I became aware of this, I was already lying on the ground, covered in dust, holding a squirming lizard firmly in my hand.

I somehow managed to convince Matin to come back, pointing at the lizard in my clenched fist. He sulked for a while and refused to talk. Then I gave him my straw hat, which he had longed for and which, by the way, fit him perfectly. Later he gave me one of his shirts in return. It was too small for me, but it had a cool secret pocket right under the armpit. What was that for? For the dagger, Matin explained.

Matin with my straw hat

It was unequivocally established and recorded in Anna Yelen's travel journal (Tout sur l'Afghanistan, Paris 1977) that, even years later, Matin still remembered the eccentric young man who chased lizards, snakes, geckos and frogs, and looked at birds through binoculars. Her book further explains that Matin considered himself an actor, because he participated in the filming of the movie "The Horsemen" with Omar Sharif and Anthony Quinn, directed by John Frankenheimer, and based on the French novel Les Cavaliers by Joseph Kessel.

I don't know that, apart from one straw hat, any trace was left of my presence in Afghanistan.

Afghanistan, on the other hand, stayed with me forever.

In my house in Belgrade, there is shallow blue bowl that has been sitting on my dining room table for the past 50 years. It was bought in the village of Istalif, north of Kabul, a place famous for its ceramic workshops. The bowl is still intact just like on the day I bought it, but the village is no longer there.