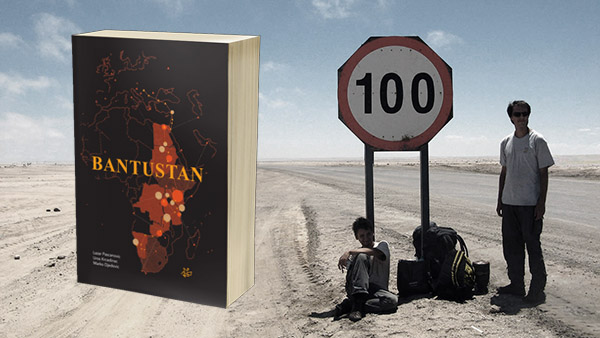

Chisinau, Moldova, photo by Ion Chibzii.

Chisinau, Moldova, photo by Ion Chibzii.

A writer from a small country, of course, looks towards the big nations, towards France, Germany, the UK... He fantasizes about countless editions of his books, even pocket editions sold at airports. Meanwhile, his experienced agent shakes his head.

- We have no chance in France, they wouldn't remember us even if they tried really hard. If you say, I have an interesting writer from Croatia, to them it sounds dangerous, like if a guy from Africa came to us and introduced himself as a writer from Mali. You immediately try to remember the phone number of the police.

- What do you mean?

- Literature is created in famous locations, and ours, between so many borders, seems too narrow even for a children's book. And as you know, no one reads short stories anymore.

- Well, what about the UK?

- Perhaps something could be done there… I do have some contacts, but so far they’ve responded to all our proposals with polite refusals. At book fairs, their agents regularly ask me if we have ever been someone's colony, and how our colonial past affected the second and third generation of our writers. They want to read about the suffering they inflicted on oppressed peoples – have you heard of the neocolonial literature?

- And Germany?

- Listen, some things cannot be changed overnight, but don't get all depressed on me now, OK? There's also Czechia, Poland, Slovakia... Let's talk about Hungary, for instance. The average circulation there is several thousand copies, which isn't so bad.

- Those new Russian writers did well here.

- With the Russians it only goes one way.

- They’ve been buying up our coastal properties…

- As I said, one way. And don't mix hotel business with translated literature.

- What else is there? Spain, Portugal, why not try there as a back door to the Latin American book market?

- In principle – yes, maybe. I sent them a preliminary list. And you, of course, are on it. Look, what I can offer you right now is Bulgaria. Don't make a face! Serbs, for example, traditionally do well there. They also want us, Croats, but on the condition that they are not mentioned in a bad light. I hope you don't have any Bulgarian villains in your novel?

- No.

- Good, that’s good. It is about ten million potential readers.

- Wait, I didn't even ask you about America.

- I'm glad you didn’t ask me about America. Because I would tell you what I always tell your fellow writers when they ask me about America. So...

***

In the Republic of Moldova, I was introduced as a famous writer from Croatia – it happened at an afternoon tea party in an elite part of Chisinau. Although my friend Branko and I actually wanted to go on a tour of the medieval monastery in Stari Orhej, a phone call from a man whom I will call Kornel (not his real name) redirected us to a hill overlooking the city, dotted with luxurious villas. We didn’t see any security, perhaps because the streets were so narrow that they could be defended by a single oligarch with a gun.

Branko, who by then had already sold the largest amount of diapers in the history of this young republic, described Kornel as a Moldovan big shot whose name opens ministerial doors. He is expensive, but extremely penetrative, as Branko put it. Kornel couldn’t have been more than thirty-five: short, stocky, fierce. He welcomed us in his opulent villa. A pale girl with a poodle in her arms was sitting in front of a giant flat TV. Kornel introduced her as Natalia. Then we went on a tour of the house filled with art and the rifles that Kornel sometimes uses to hunt foxes.

- It is healthy for business – he said.

Poor Chisinau. From the upper terrace, it looked like a rag half buried in clay, but for a moment Kornel was moved by the sight of his hometown. So he decided that we urgently needed something to drink. He said he was drinking beer to cure his hangover from last night's binge, after which Branko gave me his first worried look of the day. Kornel asked what I was doing in his wonderful country. I told him the truth: I'm shooting a ten-minute travel documentary about the cultural and social life of Chisinau.

- He is also a writer – Branko said.

- What do you write about? History?

- Well, not really...

- What then?

- Mid-life crises with passionate love affairs that take place in various cities around the world.

- Attractive – Kornel said. – And why not publish something here with us, have you thought about it? My friend has a big store in the city center. He even sells books.

- He could be the first writer from Croatia to be published in Moldova – Branko said.

- In Romanian?

- Romanian?! – Kornel glared at me. – In Moldovan, of course. Or maybe that’s beneath you?

- No, not at all. I’d love that.

Kornel then devoted himself to conversations via his cell phone. It seemed as if he had decided to arrange all the details of the publication of my book on that very late Sunday afternoon. Who would have thought that things would turn out like this. I tried to hide my excitement. Moldova might be the poorest country in Europe, but from there you can easily reach Romania, and the publishing road then bends towards France, a well-established route of love and understanding between the two Romance peoples. The big shot paced around the large room and talked for a long, long time in his mother tongue. Meanwhile, a pale girl on the other side of the room was staring at the TV screen. The short winter afternoon was drawing to a close when Kornel finally ended the conversation.

- Ok, the music is settled, we will pick up the boys from the Conservatory – he announced.

- Which boys? – Branko asked him.

- We're going to my friend’s tavern in the woods. I want you to feel the real, original Moldova.

I noticed he didn't mention my books; never mind, we've got the whole night ahead of us. Kornel and the girl with a poodle left in their giant SUV, and Branko and I followed them in our car. Four students of the State Conservatory were indeed waiting for us at the intersection, together with their instruments. Kornel sent one of them, a violinist, into our car as a guide.

- Is it possible to make a living as a musician here in Chisinau? – I asked him.

- No.

- It must be very nice here in spring and summer, when the parks turn green – I tried again.

- It is.

Following the instructions of the violinist, we took a shortcut through some villages. The heavy Bessarabian rains that had been falling until the previous day had washed away most of the road, and the car struggled at every curve. Moldovan villages without any street lighting fit perfectly into the atmosphere. People kept emerging from the darkness right into our headlights. We also saw festively dressed young men and women standing at dark village crossroads; it was a chilly Saturday night in the week before Christmas. We crossed the deserted road to Tiraspol and Odesa and entered the forest area.

Two lanes in the mud led to a large cabin. There was almost no free space around the house; it was pressed on all sides by forest. A thin man in a green uniform met us on the porch and let us in. The musicians sat on a high antique sofa next to a bread oven, each with his instrument in his arms. Natalia petted the puppy and remained silent. When Kornel came in after us, the musicians jumped to their feet and started with neutral numbers, to warm up. Violin, cello, bass and accordion. Meanwhile, the waiter took out everything he had in the fridge: pickled cucumbers, pickled carrots, pickled watermelon... Kornel explained that these are original Moldovan specialties that, unfortunately, can no longer be found in the city. Then the wine arrived. Kornel warned us that this is an above-average wine made from wild berries and that we should be careful with it. After he said this, he downed the entire glass. Then he started raving about Steven Seagal, for whose stay in Moldova he was personally responsible.

- Seagal promised to raise money and build a Moldovan Hollywood – he said. – I brought him here and introduced him to everyone, in this very cabin, and now he doesn’t return my calls!

- Maybe he lost his phone – I surmised.

- He made a fool of me.

- It’s not your fault – Branko reassured him.

- I even introduced him to the president, who received him as a friend of our country! He ate and drank here for seven days, made all kinds of promises in the media, but after that he disappeared and didn't call again. He pissed on my reputation!

In the meantime, Kornel was also getting more agitated by the music, even though the musicians were desperately trying to find a song that would make him happy. They were young and they played with their eyes wide open, obviously under stress. Soon it became clear that the problem was not the music, not even Steven Seagal: the problem was that Kornel was in a bad mood. I realized this when he asked me what I thought about his country. I said something about our shared culture that is common to all the countries in this part of the world, careful not to say anything about poverty in the streets of Chisinau.

- You don't know anything about my country – he interrupted me.

- He doesn't know much, that’s true – Branko jumped in – but he just arrived two days ago, give him time to learn.

- I wasn’t talking to you – Kornel cut him off. Then he turned back to me. – You haven’t answered my question.

I didn’t know what to say.

- He even reminds me of someone – he went on, turning to the waiter. – Does this guy look like someone to you?

- Yes – the waiter confirmed – he looks a lot like someone.

I had no idea what they were talking about, nor what was going on, except that our host was drunk.

- Branko – he said – I'm very sorry to have to tell you this, but your friend has no place at this table.

- Kornel, please, he is...

- He is a corrupt man who came to spread lies about my country. That’s what he is.

I thought it best not to aggravate him, instead trying to focus on the music. The tune the musicians were playing was light and uplifting, despite the fact that Kornel was just talking about how many Moldovan politicians thought they were better than him and now it is possible that some of them might be buried in the forests around us. He occasionally circled back to Steven Seagal, who’d do best not to set foot in Moldova ever again. That was when Branko finally realized that things were going downhill, so he asked me to step outside.

Out on the porch, the waiter was sitting and smoking, and a minute later the musicians joined him and started to smoke too. When they finished their cigarettes they told us to go back inside, which we did because we were freezing and had no idea where to go; all around there was just forest, muddy roads and not a single light in sight.

We were met by an unexpected sight in the dining room. The quiet girl with the poodle, who hadn’t uttered a word all night, was now speaking very energetically to Kornel over the remains of the dinner. We had no idea what she was saying, but it was obvious that she was angry. And Kornel just sat there in silence, staring blankly at a pickled watermelon. When she finished, Natalia put out her hands, and the poodle obediently jumped into her lap.

Kornel spent the rest of the evening in insulted silence, after which he fell asleep on the sofa, occasionally murmuring the words Steven Seagal in his sleep. That was when the musicians finally told us we could drive them home. As we were driving away from the log cabin, I looked at the dark conifers lining the road and wondered about all those Moldovan politicians who thought they were better than our host.