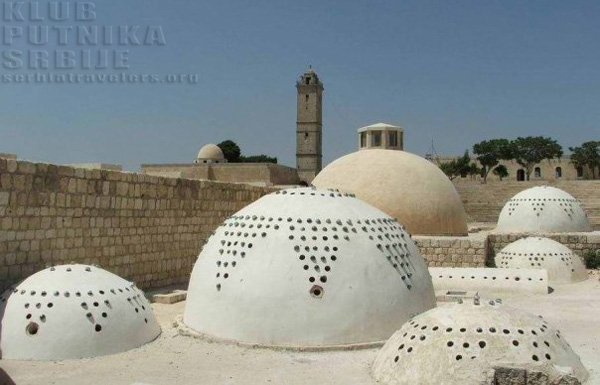

A short travelogue from Aleppo, Syria, about a rainy day, a swinging camel's head and an eightfold dad with a hi-tech cell phone.

It was a wet March, with wet trees, wet streets, wet socks in wet sneakers. We walked around the alleyways of Aleppo, among people with umbrellas, or patiently stood huddled under the small eaves of the cheese and olives vendors, with those without umbrellas. We were trying to get lost, deciding where to go next based solely upon something that, at that very moment, caught our eye. Since there was no place where we were supposed to be, we had the nagging feeling that this somehow made the whole losing game meaningless. At one point, completely by chance, we found ourselves in a semidark butcher's bazaar, among the carcasses of bloody meat, with camel heads swinging in the air, hanging in the best Freddy Kreuger style, with a bit of parsley in their mouths. In a small shop window, next to a thick hanging sausage forest, we noticed a cage with a canary; at that point a couple of worn-out cliches about life probably crossed our minds.

The rain drummed on the roof made of sheet metal, plastic, stone and whatnot, leaking here and there in form of a thin stream that carefully aimed to sneak right into the passerby's collar. Iva stood on the tips of her toes trying to take a photo of something - maybe the controversial canary - but a couple of the nearest butchers immediately shouted "madam, madam", genially drawing her attention to the fact that her shirt got untucked, revealing the belly button (if you have no belly button, wrote Dusko Radovic, you'll have a hard time proving that you were born at all). After having carefully tucked in and hidden away the compromising detail, we continued to wander about, waiting for the downpour to abate.

A huge friendly fellow with a moustache wanted to know where did we come from and what we were doing there, so we told him. He then wanted to know if we had any children, so we told him. Then he asked why not, explaining that he had eight. Lest we think that it puts a great strain on his honored wife, he obviated us by explaining that he actually had two honored wives. Do they bicker, I asked. No, he said, why would they bicker? They respect and help each other, and they love him, and he loves them, just as he loves all his children, because what would this life be without children? The house would be empty and silent, like a tomb. In the evenings, when he comes home from work, he always brings them presents, to both the kids and the wives. We listened to him thinking that the man really looked like an archetype of a daddy - sturdy, moustached, lighthearted, simple-minded, with a large pot belly and cheerful eyes.

It seemed that we were running out of conversation so, not to stand there in awkward silence, I asked him what his job was. He pointed at his bloody apron and said, I'm a butcher, but not only that, I own a butcher's shop. This here, it is my shop (not the one with the canary, but right next to it). He noticed us observing the camel head which, hanging by a rope, lazily swayed in the draft. That camel I killed yesterday, he said, would you care to see it? We didn't entirely understand how it was possible to see something that had already happened and, as such, belonged to the past, but we nodded: we would.

From one of his apron pockets the Syrian dad took out a cell phone with a large screen, fiddled around it with his thick fingers, and then stuck it into our faces.

Leaning onto the soot-covered bazaar wall, we look at the colourful lit screen and we see: a stone-paved square, some old cube-shaped houses, a bunch of people standing and watching with curiosity. In the center of the square there's a big camel, and next to it our friend the dad who, as we worriedly realise, is not the camel's friend, because he holds a huge saber in his relaxed arm.

Like in a strange, archaic dream, we see the dad swinging the saber and hitting the long neck of the camel, which lets out a horrible cry (delivered to us through the advanced technology of sophisticated digital cell phone sound) and falls to its knees. One more stroke, the camel is lying on the ground, the dad standing next to it. The recording ends and the dad switches off the cell phone, and we are abruptly transported back to the semidark butcher's bazaar, to the present, to the rainy today.

As slow milliseconds elapse, I'm asking myself what to say to our friend, an eightfold dad and a steady-handed butcher. After all, if we forget about all the folklore for a moment (saber, stone-paved square etc) - a pig or a camel - makes little difference.

Finally I opt for the local equivalent of our "good work, mister", and pat him heartily on the back, which causes a blissful grin on his part. Then we carefully listen to the patter coming from above, hoping against the odds that the downpour will eventually have to stop, wondering why couldn't we, by the same sheer coincidence, have wandered into, say, the sweets bazaar instead.